The Art of Seeing: How Master Storytellers Hone Their Craft Through Observation and Practice

In a world saturated with noise, the ability to truly see—both literally and metaphorically—has become a rare and invaluable skill. For master storytellers, seeing goes beyond the mere act of looking. It’s about noticing details, patterns, and connections that others might overlook and transforming them into narratives that resonate and linger in the minds of an audience. This skill isn’t innate; it’s cultivated through deliberate practice, reflection, and a deep curiosity about the human experience.

Observation: The Cornerstone of Storytelling

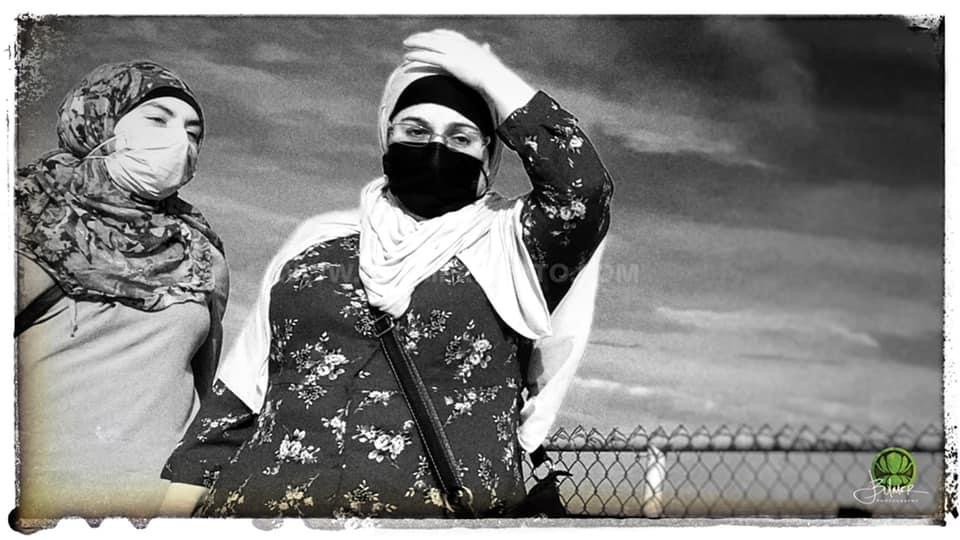

At the heart of every compelling story lies a sharp eye for detail. Whether through words, photographs, or film, storytellers use observation to uncover the extraordinary in the ordinary. Master storytellers train themselves to notice the flicker of emotion in someone’s eyes, the interplay of light and shadow in a quiet room, or the rhythm of footsteps on a bustling street. These seemingly insignificant moments are the raw material for narratives that feel authentic and emotionally rich.

To hone their craft, storytellers engage in practices that heighten their observational skills. Slowing down is often the first step. In today’s fast-paced world, distractions—phones, emails, and the endless stream of content—blind us to what’s right in front of us. Walking without headphones, sitting quietly in a park, or simply pausing to take in a scene allows storytellers to engage their senses fully. They tune in to the sounds of overlapping conversations, the subtle variations in color and texture, and the way light changes over the course of a day.

The Practice of Seeing

Master storytellers often carry journals to document their observations. This practice sharpens their ability to notice and articulate details. For instance, noting how a neighborhood shifts from the quiet of dawn to the buzz of midday and the calm of evening reveals not only the passage of time but also the essence of a place. Sketching, photographing, or writing about these changes trains storytellers to see patterns and relationships that deepen their work.

Exercises like observing a busy street corner or a food court teach storytellers to notice movement, interaction, and atmosphere. How do people pause, linger, or brush past one another? What do their gestures, postures, and expressions reveal about their moods or relationships? By asking these questions, storytellers learn to weave small observations into rich, textured narratives.

Learning from the Masters

Even the most skilled storytellers draw inspiration and lessons from others. They study the techniques of master writers, photographers, and filmmakers to understand how small details build emotional and narrative depth. For instance, a writer might analyze how a favorite author describes a setting to create mood and tone, or a filmmaker might study the use of shadows and framing in a classic movie scene.

Some storytellers take this learning further by replicating the techniques of others. A photographer might attempt to emulate the lighting style of a renowned artist, not to copy their work but to better understand how it shapes emotion and focus. Similarly, a writer might rewrite a beloved passage, experimenting with different details to see how they affect the story’s impact.

Turning Observation Into Stories

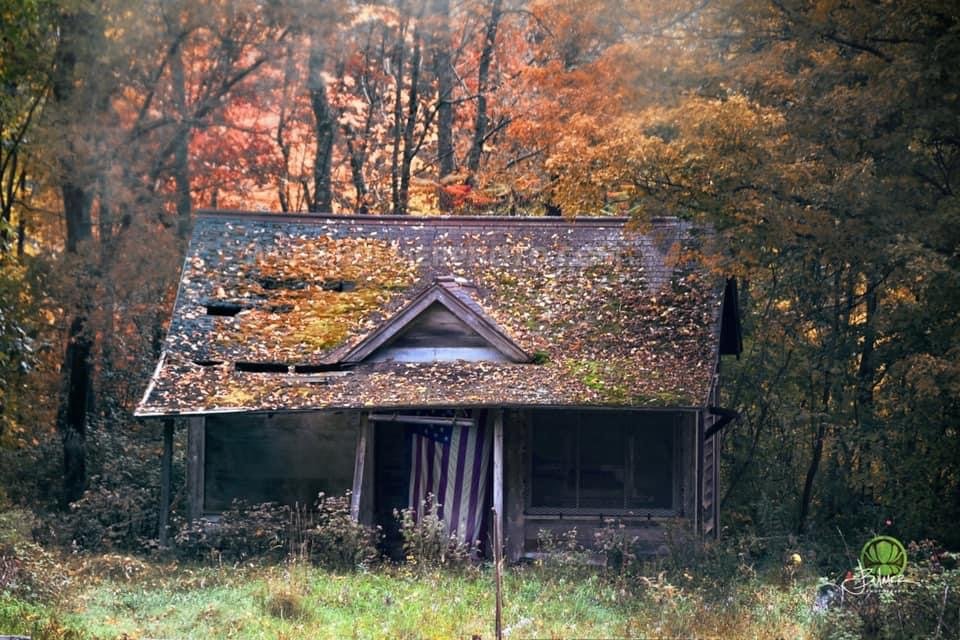

The power of observation lies in its application. In writing, rich descriptions replace generic phrases, immersing readers in vivid worlds. A simple sunset becomes a symphony of colors and shadows that reflects a character’s inner turmoil. In photography, a peeling wall or the reflection in a puddle becomes a metaphor for resilience or nostalgia. In filmmaking, background elements—like the flicker of a neon sign or the clutter on a character’s desk—add layers of meaning to a scene.

Master storytellers also pay attention to time. Documenting a single location at different hours reveals how light, activity, and mood transform a space. Morning might bring softness and stillness, while evening introduces bold contrasts and lively energy. These temporal shifts add authenticity and depth to their stories.

Observation as a Lifelong Practice

What sets master storytellers apart is their commitment to lifelong observation. They don’t wait for inspiration; they seek it in the world around them. They look for stories in the mundane, the overlooked, and the fleeting. Whether sitting on a park bench, watching the ebb and flow of people, or listening to the cadence of conversations in a café, they remain attuned to the world’s rhythms and nuances.

Storytelling isn’t just about what’s seen—it’s about what’s felt and understood. The flicker of recognition in a stranger’s eyes, the way shadows dance on a wall at dusk, or the subtle tension in a crowded room—all these moments hold potential for connection and meaning.

The Power of Stories Built on Observation

The ability to see and translate observations into stories is what sets great storytellers apart. In an age of constant content, stories rooted in sharp observation stand out. They connect on a deeper level, evoking emotions and painting vivid pictures that linger long after the final word or frame.

The next time you find yourself in a familiar space, pause. Look closer. There’s always a story waiting to be discovered. Master storytellers know this truth, and they embrace it with curiosity and intent. By sharpening your ability to see, you not only enrich your creative work but also deepen your connection to the intricate tapestry of life itself.

Exercises to Practice Observation Skills for Writing

Detail Journaling: Spend 15 minutes in a location (park, café, bus stop) and write down every detail you notice: colors, sounds, smells, and textures. Focus on sensory specifics rather than general descriptions.

Character Sketches: Observe a stranger and write a brief character profile. Imagine their backstory, motivations, and emotions based on their body language, clothing, or actions.

One-Object Story: Choose a random object (e.g., a coffee mug or an old photograph) and describe it in detail. Then, write a story where the object plays a significant role.

Scene Evolution: Observe a location at three different times of the day (morning, afternoon, and night). Note how the atmosphere, lighting, and interactions change over time.

Dialogue Snippets: Eavesdrop (respectfully) on snippets of conversation in public places. Write down fragments and imagine the context or extend the dialogue into a full scene.

Word-Painting Exercise: Take a photograph or painting and describe it vividly using only words. Focus on capturing the mood, details, and essence of the image.

Five-Sense Challenge: Spend time in a setting and document at least one observation for each of the five senses. Push yourself to notice subtle or overlooked sensory details.

Reverse Perspectives: Write a scene from two different perspectives. For example, describe a market from the view of a customer and then from the perspective of a vendor.

Emotion Mapping: Watch people’s faces in a public space and note their emotions. Write down how subtle shifts in expression (a raised eyebrow, a slight frown) communicate feelings.

Walk and Write: Go for a 10-minute walk and write about everything you noticed upon your return. Challenge yourself to remember small details like street signs, sounds, or peculiarities.

Exercises to Practice Observation Skills for Photography and Video

Light Study: Spend an hour observing how light interacts with a subject. Photograph the same object at different times of the day to capture changes in mood, shadow, and texture.

Composition Walks: Choose a compositional theme (e.g., symmetry, leading lines, or contrast) and take photos that focus exclusively on that element during a walk.

Texture Hunt: Photograph a series of textures (e.g., peeling paint, rough stone, smooth glass) and experiment with how framing and angles emphasize their qualities.

Micro to Macro: Choose a single subject and photograph it from varying distances and perspectives. Capture its details up close, then step back for a wider context.

Silent Video Observation: Shoot a short silent video in one location. Focus on capturing the mood and story using only visuals, such as movement, light, and framing.

Shadow and Silhouette Challenge: Look for opportunities to capture shadows or silhouettes in your environment. Experiment with angles and contrast to create dramatic effects.

Time-Lapse Observation: Create a time-lapse video of a space over an hour or a day. Notice and document how activity, light, and atmosphere shift during that period.

Reflections and Frames: Find reflections (in water, mirrors, or windows) and use them to frame or enhance your composition. Experiment with how they distort or emphasize your subject.

Story in 5 Shots: Tell a complete story using only five photos or video clips. Plan the sequence carefully: establish context, introduce a character, and resolve a narrative.

Color Focus: Choose a single color and document how it appears in your environment. Use photography or video to highlight how it creates harmony or contrast within a scene.

By consistently practicing these exercises, writers and visual storytellers can sharpen their ability to observe and translate the world around them into evocative narratives.

About the Author

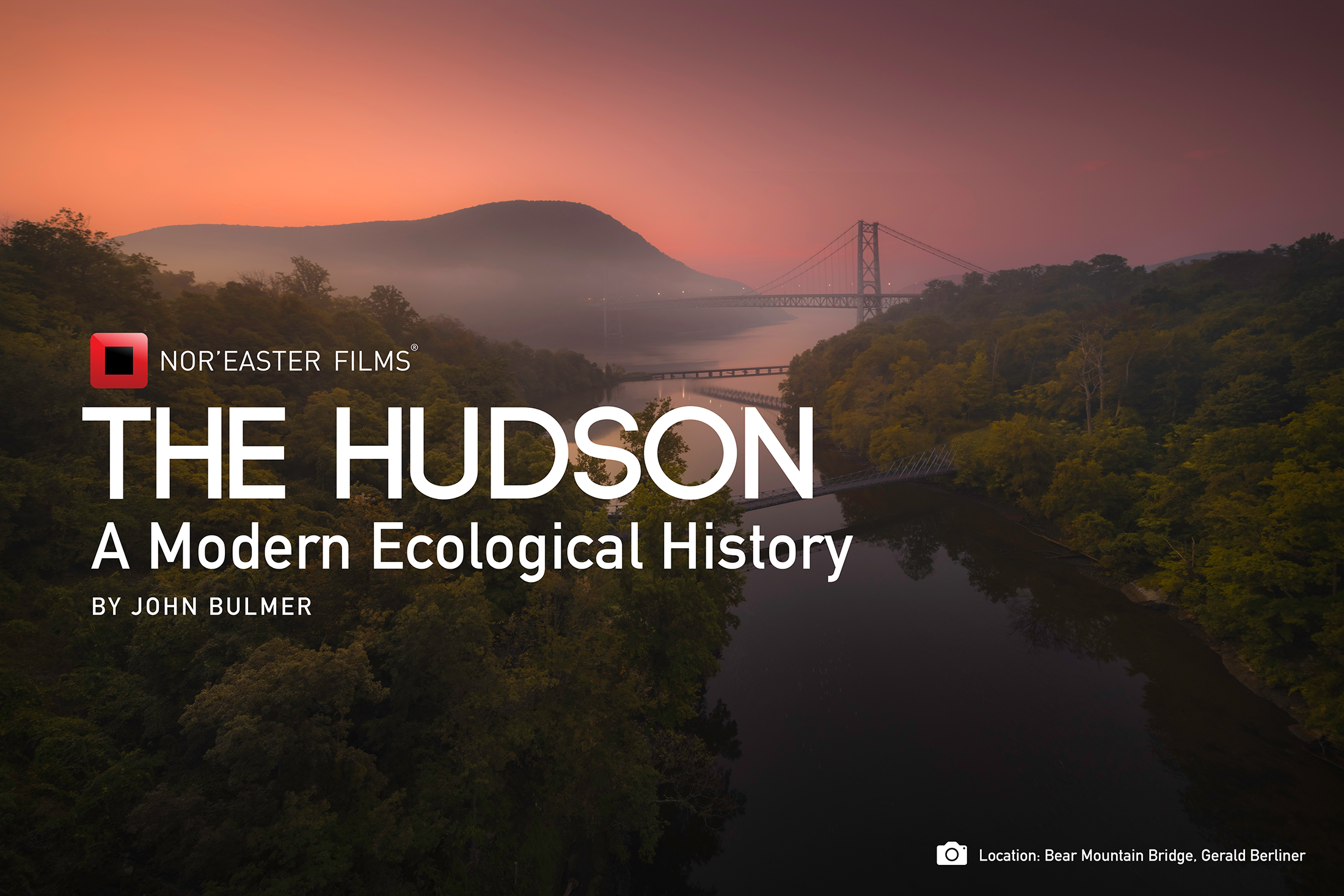

John Bulmer is a photographer, filmmaker, storyteller, and photo historian based in Saratoga, New York. Through his ventures, John Bulmer Photography and Nor’easter Films, John specializes in creating compelling commercial and editorial photography, as well as impactful video projects. His work has been featured in numerous publications, including The New York Times.

A seasoned photojournalist, John is also the founder of Adirondack Mountain News, a platform providing comprehensive reporting on wilderness conservation, regional history, and outdoor advocacy. His photography and writing often emphasize the intersection of creativity and environmental stewardship, advocating for sustainable practices and the protection of fragile ecosystems.

John’s dedication to the art of storytelling extends to public speaking and education, where he collaborates with institutions like Columbia University and photography societies to share his expertise in crafting visual narratives and working in challenging environments.

When not behind the lens, John is actively involved in the wilderness and search-and-rescue community, serving as a public information officer and advocate for outdoor safety and accessibility.

Adirondack Mountain News | John Bulmer Media | John Bulmer Photography | Nor’easter Films

Image: Christopher Burns/Unsplash

@2024 John Bulmer Media, John Bulmer Photography and Nor’easter Films. All Rights Reserved.